The founders of Radley College were heavily influenced by the liturgical reforms of the Oxford Movement. These included many sung elements such as anthems led by a trained choir. An essential adjunct for sacred music was a pipe organ. In 1847, there was a growing demand by churches for new or refurbished organs. Sewell and Singleton were absolutely determined that Radley should not only have an organ but that it should be one of the finest that could be constructed. Singleton commissioned Telford’s of Dublin to build an organ at a cost of £2,000, considerably more than the original estimate for the chapel itself. It was installed in 1848 after it had been demonstrated to large crowds in Dublin. Singleton was thrilled with the new instrument:

‘Telford is utterly amazed at its stupendous power and says there is nothing like it anywhere that he has been. He has heard several organs lately in England, and they all seem to him to be thin and hungry compared with this. In fact, ours sounds very glorious.’ Singleton’s diary, 11th September 1848.

Telford regarded it as his best work to date, and he arranged for it to be shipped back to Dublin for the 1853 Exhibition at his own expense (compensating the College by adding a Pedal 32′ stop on its return).

This organ was far too large for the original Chapel, three manuals and 45 stops. It must have sounded immense in such a small building, although how much credence we can give to the claim that ‘the two “doubles” [16′ stops] have had the honour to make some ladies sick in their stomachs’ is doubtful. The description of the organ

In essence, this instrument survived until 1938, but it grew and grew, aided and abetted by George Wharton, precentor from 1862 until 1914, who began to expand the organ almost by stealth, encouraging donations of individual stops. It quickly expanded to 4 manuals and 60 stops – a staggering number for the size of the building – and even to 5 manuals by 1883, making it significantly bigger than most cathedral organs of the time. In 1889, it was converted to run powered by a Crossley gas engine – having previously been operated by a chapel servitor pumping the bellows.

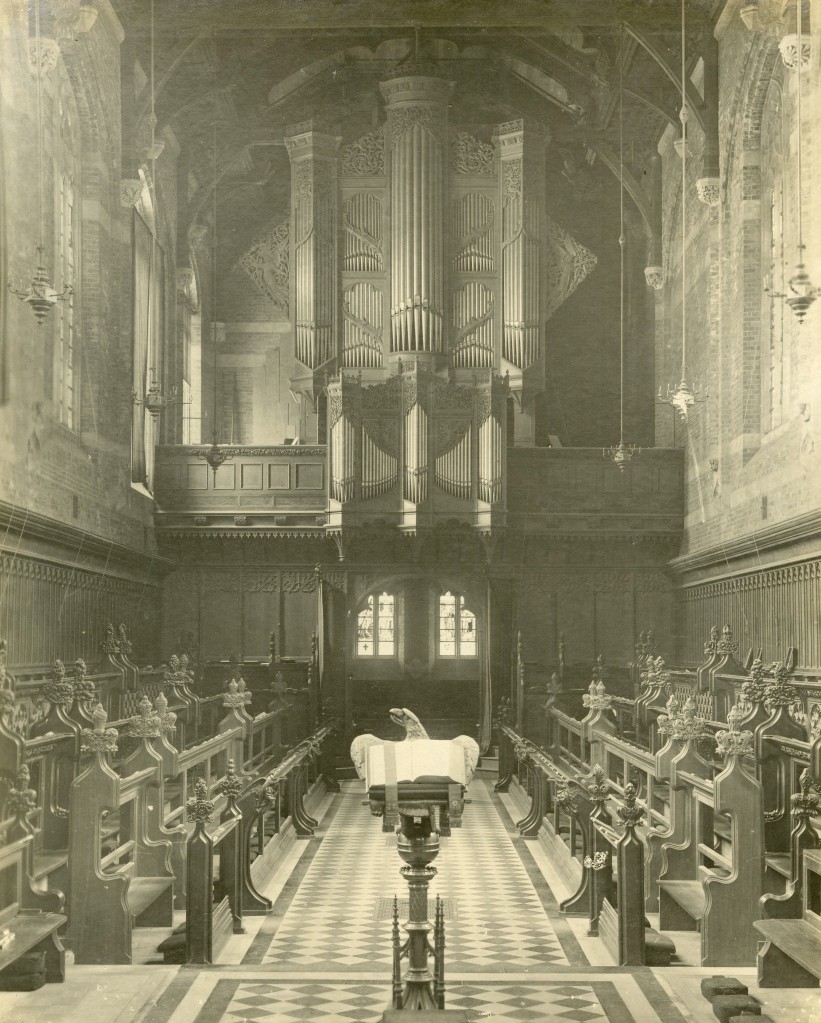

When the new chapel was built in 1895, the organ was transferred largely unaltered. Sir Thomas Jackson designed a new case, occupying much of the west gallery, but the opportunity was not taken to carry out a full overhaul and the reliability of the organ gave concern almost immediately.

In 1939, Rushworth & Dreaper were engaged to build a new instrument. Some of the old stops were retained, including the pedal 32′, although the latter was hugely disadvantaged by being placed underneath the new gallery seating, where the longest pipes had to be reduced in length by a process known as ‘Haskelling’. The remainder was placed in two chambers, one cutting into the southwest corner of Chapel Quad, and the other facing towards G Social. The Rushworth & Dreaper organ was smaller than its predecessor. Because it was in two places – neither of which was ideal for playing it – the console was separate from the organ, with electric action.

By the 1970s this organ had, in its turn, become unreliable. Electric organ actions are more prone to failure than mechanical ones, especially those built with 1930s technology. In any case, the organ had never really been as good as hoped, and its solution of loud, high pressure stops boxed into chambers was very unfashionable. A plan was therefore made to build a new organ, which was to be voiced in a completely different style, essentially that of the 18th century, with mechanical action. It was completed by Hill, Norman & Beard in 1980.

It must have been a revelation after the sound of the 1938 instrument – fresh, clean and sparkling – but it immediately became clear it was too quiet: too quiet even if it had been placed back in the centre of the west gallery, able to speak clearly down the length of the chapel. But its position to one side proved a fatal compromise between the desire to allow the organ to speak freely in the chapel and the constant need for space for boys. In the end, only part of the main Great manual pipework encroached into the main building; the rest was confined to the old main chamber.

The immediate solution was to re-use part of the old Choir organ in the chamber opposite G social. This had been left intact, and some of it – along with second hand pipework from Hill, Norman & Beard – was reconnected to form the East organ. This screamed at the unlucky boys who, after the seating changes of 1995, sat inches from it, but it did at least mean that hymn singing was supported properly, even if it was always out of tune in the winter. The organ itself was not unsuccessful, as long as you sat in the gallery, where recital audiences were always placed. It was rather heavy to play – some electrical assistance was added early on, which helped, but it was a workout all the same.

The decision to extend the chapel in 2020–21 allowed a completely fresh approach. Nicholson & Co of Malvern were commissioned to build a new organ. At last, there was room again in the west gallery, where it can speak freely down the length of the building; and a wholly new instrument allows for more robust voicing – new, apart from one rank of pedal pipes surviving, incredibly, from at least 1868.

The style of the new organ is in many ways a nod to the 19th century, with a Romantic voicing style, and a gothic case and console reminiscent in many ways of the 1895 instrument. The majority of the organ is in the new case, in the centre of the gallery, with some of the larger pedal pipes cunningly concealed behind a screen in the old organ chamber. The challenge was to support a wide range of volume, from a single chorister singing a solo to the entire school in full cry – a challenge which the new organ takes on triumphantly.

A virtual visit to Nicholson & Co of Malvern

All four of Radley’s organs are listed on the National Pipe Organ Register

Tim Morris, Succentor

February 2022